African Americans literally created #MemorialDay. Here's how it went down. pic.twitter.com/Y4fs4NtbrV

— The Root (@TheRoot) May 26, 2018

Descendants of Civil War Veterans

Baldy Guy (1841-1911) & George Guy (1845-1928)

2011 Guy Family Reunion T-Shirt (front)

2011 Guy Family Reunion T-Shirt (back)

www.afroamcivilwar.org

The 2015 GUY FAMILY REUNION Co-Chairpersons will present a CIVIL WAR theme at next year's reunion honoring our two GUY Family ancestors who served in the Civil War:

BALDY GUY and his younger brother GEORGE GUY

(Baldy & George fought in the Battle of Brice's Cross Roads on June 10, 1864.)

Brigadier General Samuel D. Sturgis was the Commanding Officer of Baldy Guy and George Guy in the Civil War. In June 1864 he was routed by Nathan Bedford Forrest at the Battle of Brice's Crossroads in Mississippi, an encounter that effectively ended his Civil War service.

Baldy Guy (1841-1911) was a Union soldier in the Civil War. His military service was between 22 May 1863 to 31 Dec 1865. Baldy Guy was a Private in Company B, 55th Regiment United States Colored Volunteer Infantry. He was wounded in the Battle of Brice's Cross Roads on June 10, 1864 near Guntown, Mississippi. Baldy Guy suffered a gun shot wound in the left shoulder. His Pension Certificate Number was 981883.

George Guy (1845-1928) was a Union soldier in the Civil War. His military service was between 22 May 1863 to 31 Dec 1865. George Guy was a Private in Company H, 55th Regiment United States Colored Volunteer Infantry. He fought in the Battle of Brice's Cross Roads on June 10, 1864 near Guntown, Mississippi. His Pension Certificate Number was 1152810

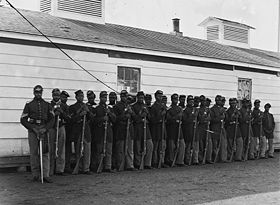

United States Colored Troops Infantry

55th Regiment Infantry

Organized March 11, 1864, from 1st Alabama Infantry (African Descent). Attached to 1st Colored Brigade, District of Memphis, Tenn., 16th Corps, to April 1864. Fort Pickering, Post and Defenses of Memphis, District of West Tennessee, to June, 1864. 3rd Brigade, Infantry Division, Sturgis' Expedition, to June, 1864. 1st Colored Brigade, District of Memphis, Tenn., District of West Tennessee, to January, 1865. 2nd Brigade, Post and Defenses of Memphis, Tenn., to February, 1865. 2nd Brigade, United States Colored Troops, District of Morganza, La., Dept. of the Gulf, to April, 1865. District of Port Hudson, La., Dept. of the Gulf, to December, 1865.

SERVICE.--Post and garrison duty at Memphis, Tenn., until June 1, 1864. Sturgis' Expedition from Memphis into Mississippi June 1-13. Battle of Brice's Cross Roads, near Guntown, June 10. Ripley June 11. Davis' Mills June 12. Duty at Memphis until August 1. Smith's Expedition to Oxford, Miss., August 1-30. Action at Waterford August 16-17. Garrison duty at Memphis Tenn., until February, 1865. Ordered to New Orleans, La., February 23; thence to Morganza, La., February 28, and duty there until April. Garrison duty at Port Hudson, Baton Rouge and other points in Louisiana until December, 1865. Mustered out December 31, 1865.

The Battle of Brice's Crossroads was fought on June 10, 1864, near Baldwyn in Lee County, Mississippi, during the American Civil War. It pitted a 4,787-man contingent led by Confederate Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest against an 8,100-strong Union force led by Brigadier General Samuel D. Sturgis. The battle ended in a rout of the Union forces and cemented Forrest's reputation as one of the great cavalrymen.

The battle remains a textbook example of an outnumbered force prevailing through better tactics, terrain mastery, and aggressive offensive action. Despite this, the Confederates gained little through the victory other than temporarily keeping the Union out of Alabama and Mississippi.

[edit]Situation

Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman had long known that his fragile supply and communication lines through Tennessee were in serious jeopardy because of depredations by Forrest's cavalry raids. To effect a halt to Forrest's activities, he ordered Gen. Sturgis to conduct a penetration into northern Mississippi and Alabama with a force of around 8,500 troops to destroy Forrest and his command. Sturgis, after some doubts and trepidation, departedMemphis on June 1. Gen. Stephen D. Lee, alerted of Sturgis's movement, warned Forrest. Lee had also planned a rendezvous at Okolona, Mississippi, with Forrest and his own troops but told Forrest to do as he saw fit. Already in transit to Tennessee, Forrest moved his cavalry (less one division) toward Sturgis, but remained unsure of Union intentions.

Forrest soon surmised, correctly, that the Union had actually targeted Tupelo, Mississippi, located in Lee County, about 15 miles (24 km) south of Brice's Crossroads. Although badly outnumbered, he decided to repulse Sturgis instead of waiting for Lee, and selected an area to attack ahead on Sturgis's projected path. He chose Brice's Crossroads, in what is now Lee County, which featured four muddy roads, heavily wooded areas, and the natural boundary of Tishomingo Creek, which had only one bridge going east to west. Forrest, seeing that the Union cavalry moved three hours ahead of its own infantry, devised a plan that called for an attack on the Union cavalry first, with the idea of forcing the enemy infantry to hurry to assist them. Their infantry would be too tired to offer real help and the Confederates planned to push the entire Union force against the creek to the west. Forrest dispatched most of his men to two nearby towns to wait.

[edit]Battle

At 9:45 a.m. on June 10, a brigade of Benjamin H. Grierson's Union cavalry division reached Brice's Crossroads and the battle started at 10:30 a.m. when the Confederates performed a stalling operation with a brigade of their own. Forrest then ordered the rest of his cavalry to converge around the crossroads. The remainder of the Union cavalry arrived in support, but a strong Confederate assault soon pushed them back at 11:30 a.m., when the balance of Forrest's cavalry arrived on the scene. Grierson called for infantry support and Sturgis obliged. The line held until 1:30 p.m. when the first regiments of Federal infantry arrived.

The Union line, initially bolstered by the infantry, briefly seized the momentum and attacked the Confederate left flank, but Forrest launched an attack from his extreme right and left wings, before the rest of the federal infantry could take to the field. In this phase of the battle, Forrest commanded his artillery to unlimber, unprotected, only yards from the Federal position, and to shell the Union line with grapeshot. The massive damage caused Sturgis to re-order the line in a tighter semicircle around the crossroads, facing east.

At 3:30, the Confederates in the 2nd Tennessee Cavalry assaulted the bridge across the Tishomingo. Although the attack failed, it caused severe confusion among the Federal troops and Sturgis ordered a general retreat. With the Tennesseans still pressing, the retreat bottlenecked at the bridge and a panicked rout developed instead. The ensuing wild flight and pursuit back to Memphis carried across six counties before the exhausted Confederates retired.

[edit]Aftermath

The Confederates suffered 492 casualties to the Union's 2,164 (including 1,500 prisoners). Forrest captured huge supplies of arms, artillery, and ammunition as well as plenty of stores. Sturgis suffered demotion and exile to the far West. After the battle, the Union Army again accused Forrest of massacring black soldiers. However, historians believe that charge unwarranted, because later prisoner exchanges undermined the Union claim of disproportionate death.

The following is a list of artillery pieces captured by Forrest:[1]

- One 3-inch steel gun, rifled

- Three 6-pounder James bronze guns, rifled

- Two 3.8-inch James bronze guns, rifled

- Five 6-pounder bronze guns

- Two 12-pounder bronze howitzers

- Three 12-pounder Napoleon bronze guns

[edit]Factors leading to the Union loss

In correspondence with General Sturgis, Colonel Alex Wilkin, commander of the 9th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment gave several reasons for the loss of the battle.[2] He stated that General Sturgis, knowing that his men were under-supplied, having been on less than half rations, had been hesitant to advance on the enemy, but had done so against his better judgment because he had been ordered to do so. When the cavalry had engaged the enemy, many of the infantry had been ordered to advance double-time to support the cavalry, and in their weakened condition, many had fallen out in the advance. Those who did arrive were exhausted at the beginning of the battle, while the Confederates were fresh, and well fed owing to a large supply in their rear.

The roads were also wet due to a recent rain storm, that slowed the advance of the supply wagons and ammunition train, and several men were employed to try to make the roads passable. Additionally, the horses pulling the trains were poorly fed because there was little in the way of forage for them to eat along the way. This accounted for Forrest's capture of the artillery and supplies.

Intelligence had entirely favored the South, because the Confederates had been constantly fed information about the position and strength of the Union army from civilians in the area, while Sturgis had received no such intelligence. Because of this information, the South had been able meet the Union Army at a place where they could ambush Sturgis and make retreat as difficult as possible (Tishomingo Creek was in their rear with only a single bridge as a crossing point.) This place was close to the Confederate supply depot, and very far from the Union's.

When the retreat had occurred, with food and supplies exhausted, many of the Union soldiers were unable to retreat with the rest because of fatigue. This was much of the reason why so many Union soldiers were captured during the battle.

Finally, Wilkin stated that the rumors that Sturgis had been intoxicated during the battle were entirely false.

[edit]Battlefield today

The battle is commemorated at Brices Cross Roads National Battlefield Site, established in 1929. The National Park Service erected and maintains monuments and interpretive panels on a small 1-acre (4,000 m2) plot at the crossroads. This is the spot where the Brice family house once stood. The Brice's Crossroads Museum is in Baldwyn, Mississippi, just over a mile from the battlefield. Brice's Crossroads is considered one of the most beautifully preserved battlefields of the Civil War.

In 1994 concerned local citizens formed the Brice's Crossroads National Battlefield Commission, Inc., to protect and preserve additional battlefield land. With assistance from the Civil War Preservation Trust(formerly the APCWS and the Civil War Trust), and the support of Federal, State, and local governments, the BCNBC, Inc. has purchased for preservation over 800 acres (3.2 km2) of the original battlefield. Much of the land purchased came from the Agnew Family in Tupelo who still owns some of the battlefield property.

The modern Bethany Presbyterian Church sits on the southeast side of the crossroads. At the time of the battle this congregation's meeting house was located further south along the Baldwyn Road. However, the Bethany Cemetery adjacent to the Park Service monument site predates the Civil War. Many of the area's earliest settlers are buried here. The graves of more than 90 Confederate soldiers killed in the battle are also located in this cemetery. Union dead from the battle were buried in common graves on the battlefield, but were later reinterred in the National Cemetery at Memphis, Tennessee.

The roads that form Brice's Crossroads lead to Baldwyn, Tupelo, Ripley, and Pontotoc, Mississippi. Tupelo is the county seat for historic Lee County, Mississippi. The roads, paved today, are still a major route into Lee, Prentiss, and Union counties, with thousands of cars traveling through the national battlefield to reach other destinations.

[edit]Notes

- ^ O.R., Series I, Vol. XXXIX, Part 1, p. 227.

- ^ "Minnesota in the Civil and Indian Wars, 1861-1865 pp.473".

[edit]References

- National Park Service battle description

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

[edit]External links

Click the link below to view the

Battle of Brice's Cross Roads

Civil War Museum

www.civilwaralbum.com/misc/brice1.htm

|

|

|

African American Civil War Memorial Freedom Foundation and Museum Washington, DC click on the link below: Civil War Memorial Guy Family Members and other Descendants that served in the Civil War:

Baldy Guy, Company B, 55th Regiment United States Colored Volunteer Infantry Length of service: 22 May 1863 to 31 Dec 1865 Rank of Private in the Union Army George Guy, Company H, 55th Regiment United States Colored Volunteer Infantry Length of service: 22 May 1863 to 31 Dec 1865 Rank of Private in the Union Army Henry Guy, Company A, 55th Regiment United States Colored Volunteer Infantry Length of service: 22 May 1863 to 31 Dec 1865 Rank of Private in the Union Army Daniel Saulsberry Sr. Company G, 11th Regiment United States Colored Volunteer Infantry Length of service: 1 Apr 1864 to 12 Jan 1866 Rank of Sergeant in the Union Army Ransom Scott, Company D, 50th Regiment United States Colored Volunteer Infantry Length of service: 27 Jul 1863 to 20 Mar 1866 Rank of Private in the Union Army Peter Price, Company A, 63rd Regiment United States Colored Volunteer Infantry Length of service: 11 Mar 1864 to 9 Jan 1866 Rank of Sergeant in the Union Army Henderson Price, Company G, 55th Regiment United States Colored Volunteer Infantry Length of service: 22 May 1863 to 31 Dec 1865 Was a 9 year old Musician in the Union Army Jeremiah Tate (Prophet), Company E, 55th Regiment United States Colored Volunteer Infantry Length of service: 22 May 1863 to 31 Dec 1865 Rank of Private in the Union Army |

United States Colored Troops

The United States Colored Troops (USCT) were regiments of the United States Army during the American Civil War that were composed of African-American ("colored") soldiers. The men of the USCT were the forerunners of the famous Buffalo Soldiers.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] History

The U.S. Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act[1] in July 1862 that freed slaves of owners in rebellion against the United States, and a militia act that empowered the President to use freed slaves in any capacity in the army. President Abraham Lincoln, however, was concerned with public opinion in the four border states that remained in the Union, as well as with northern Democrats who supported the war. Lincoln opposed early efforts to recruit black soldiers, even though he accepted their use as laborers. Union Army setbacks in battles over the summer of 1862 forced Lincoln into the more drastic response of emancipating all slaves in states at war with the Union. In September 1862 Lincoln issued his preliminary proclamation that all slaves in rebellious states would be free as of January 1. Recruitment of colored regiments began in full force following the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863.[2]

The United States War Department issued General Order Number 143 on May 22, 1863, establishing a "Bureau of Colored Troops" to facilitate the recruitment of African-American soldiers to fight for the Union Army.[3] Regiments, including infantry, cavalry, light artillery, and heavy artillery units, were recruited from all states of the Union and became known as the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Approximately 175 regiments of over 178,000 free blacks and freed slaves served during the last two years of the war, and bolstered the Union war effort at a critical time. By war's end, the USCT were approximately a tenth of all Union troops. There were 2,751 USCT combat casualties during the war, and 68,178 losses from all causes.[4]

USCT regiments were led by white officers and rank advancement was limited for black soldiers. The Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments in Philadelphia opened a Free Military Academy for Applicants for the Command of Colored Troops at the end of 1863.[5] For a time, black soldiers received less pay than their white counterparts.[6] Notable members of USCT regiments included Martin Robinson Delany, and the sons of Frederick Douglass. Soldiers who fought in the Army of the James were eligible for the Butler Medal, commissioned by that army's commander, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler.

[edit] Notable actions

USCT regiments fought in all theaters of the war, but mainly served as garrison troops in rear areas. The most famous USCT action took place at the Battle of the Crater during the Siege of Petersburg, where regiments of USCT suffered heavy casualties attempting to break through Confederate lines. Other notable engagements include Fort Wagner and the Battle of Nashville. USCT soldiers often became victims of battlefield atrocities, most notably at Fort Pillow.[7] The prisoner exchange cartel broke down over the Confederacy's position on black prisoners of war. Confederate law stated that blacks captured in uniform be tried as slave insurrectionists in civil courts—a capital offense[citation needed]. Although this rarely, if ever, happened, it became a stumbling block for prisoner exchange. USCT soldiers were among the first Union forces to enter Richmond, Virginia, after its fall in April 1865. The 41st USCT regiment was present at the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox. Following the war, USCT regiments served as occupation troops in former Confederate states.

[edit] Awards

Sergeant Major Christian Fleetwood was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions with the 4th USCT in the Battle of Chaffin's Farm in Virginia. Fleetwood took up the regimental colors after 11 other USCT soldiers had been shot down while carrying them forward. Many USCT soldiers won some of the nation's highest awards. Sergeant William Harvey Carney of the 54th Massachusetts was another African American Medal of Honor recipient.

[edit] Postbellum and legacy

After the war many USCT veterans struggled for recognition and had difficulty obtaining the pensions rightful to them. The Federal government did not address the inequality until 1890 and many of the veterans did not receive service and disability pensions until the early 1900s. The history of the USCT's wartime contribution was kept alive within the black community by historians such as W. E. B. Du Bois and the subject has enjoyed a recent surge in literature.

The motion picture Glory, starring Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman and Matthew Broderick, depicted the African-American soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment during their training and several battles, including the second assault on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863.[8]

A national celebration in commemoration of the service of the United States Colored Troops was held in September 1996. A national museum is located at 1200 U Street, NW, Washington, D.C. The African American Civil War Memorial, featuring Spirit of Freedom by sculptor Ed Hamilton, is located nearby, at the corner of Vermont Avenue and U Street, NW.

[edit] Numbers of United States Colored Troops by state, North and South

| North[citation needed] | Number | South[citation needed] | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | 1,764 | Alabama | 4,969 |

| Colorado Territory | 95 | Arkansas | 5,526 |

| Delaware | 954 | Florida | 1,044 |

| District of Columbia | 3,269 | Georgia | 3,486 |

| Illinois | 1,811 | Louisiana | 24,502 |

| Indiana | 1,597 | Mississippi | 17,869 |

| Iowa | 440 | North Carolina | 5,035 |

| Kansas | 2,080 | South Carolina | 5,462 |

| Kentucky | 23,703 | Tennessee | 20,133 |

| Maine | 104 | Texas | 47 |

| Maryland | 8,718 | Virginia | 5,723 |

| Massachusetts | 3,966 | ||

| Michigan | 1,387 | Total from the South | 93,796 |

| Minnesota | 104 | ||

| Missouri | 8,344 | At large | 733 |

| New Hampshire | 125 | Not accounted for | 5,083 |

| New Jersey | 1,185 | ||

| New York | 4,125 | ||

| Ohio | 5,092 | ||

| Pennsylvania | 8,612 | ||

| Rhode Island | 1,837 | ||

| Vermont | 120 | ||

| West Virginia | 196 | ||

| Wisconsin | 155 | ||

| Total from the North | 79,283 | ||

| Total | 178,895 |

[edit] See also

- List of United States Colored Troops Civil War Units

- Marching Song of the First Arkansas

- Fort Pocahontas

- 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

- 92nd Infantry Division (United States)

- 93d Infantry Division (United States)

- 366th Infantry Regiment (United States)

- Tuskegee Airmen

- 761st Tank Battalion (United States)

[edit] Notes

- ^ Rodriguez, Junius P. Slavery in the United States: a Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 2007, vol. 2, pg 241

- ^ Cornish, The Sable Arm, pp. 29-111.

- ^ Cornish, The Sable Arm, p. 130.

- ^ Cornish, The Sable Arm, p. 288; McPherson, The Negro's Civil War, p. 237.

- ^ Cornish, The Sable Arm, p. 218.

- ^ McPherson, The Negro's Civil War, Chapter XIV, "The Struggle for Equal Pay," pp. 193-203.

- ^ Cornish, The Sable Arm, pp. 173-180.

- ^ See the film review by historian James M. McPherson, “The ‘Glory’ Story,” The New Republic, January 8 & 15, 1990, pp. 22-27.

[edit] References

- Dudley Taylor Cornish, The Sable Arm: Negro Troops in the Union Army, 1861-1865 (1956; New York: W.W. Norton, 1965).

- James M. McPherson, The Negro's Civil War: How American Negroes Felt and Acted During the War for the Union (New York: Pantheon Books, 1965).

[edit] External links

- United States Colored Troops in the Civil War

- United States Colored Troops US Army

- African Americans in the U.S. Army

- Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Black Soldiers

- 1863 Picture and News Report on the First Colored Regiment in the US

- African American Civil War Memorial and Museum

- 5th United States Colored Infantry [1]

- 8th USCT

- 19th USCT

- 35th USCT (previously the 1st North Carolina Colored Volunteers)

- 54th Massachusetts

|

||